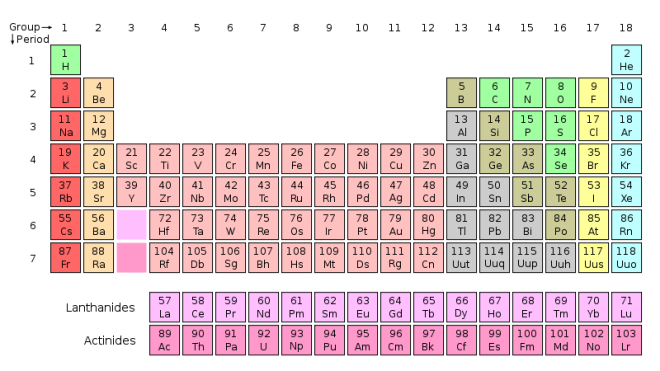

A few years ago, the poet Charles Bernstein read at Smith College in Northampton, MA. The event happened to take place in a science hall; a gigantic image of the periodic table of the elements loomed over the stage. When Bernstein got up to read, instead of turning to his manuscript, he raised his face to the chart and began to recite the table:

“Huhh!” “Hheeeee!” “Lihhhhhhhhh, Lie!”

“Be!!”

“Buh, Cuh, nnnN … Oh.”

(“Eff!”)

What!? Sound revealed as an element of the elements! A music of the spheres? Yet the sounds uttered were human, guttural, raw—elemental. Residing in the gaps between the units of the grid was deep feeling that Bernstein contacted and brought forth. We witnessed, not a recitation after all, but a magic, a creation. Bernstein recombined the basic stuff of physical being into a new kind of matter: a poem.

Instead of following a linear narrative or a related sequence of images, this poem relied for its meaning on chance, juxtaposition, sound, sound-texture, rhythm, and the release of unqualified emotion. The poem could be considered “abstract.” Just as painting can be about the paint itself—its physical and emotional qualities—and not about what the paint is representing, poetry can use the sonorous and even visual properties of words to affect us. It does not need to rely only on what words do in their typical settings of grammar and syntax. These qualities are present in all poetry and art, though they can be easy to overlook in favor of the explanation or description we usually think of as “meaning.”

I recently heard a lecture, On the Lyric, by Norman Fischer, a Jewish Zen teacher and poet whose work, though lyrical, enters, as does Bernstein’s, the sphere of the abstract, the so-called “language poetry.” Fischer says the roots of the lyric reach back not only to the Greeks, whose rhetoric tends to tell us about the world, but also to the very different Hebrew imagination. This imagination makes a poetry, as in the psalms, that is a private conversation between the poet and “God,” the unknowable. A reader of such poetry becomes party to these conversations. But we are not being spoken to directly; we are being allowed to overhear a sacred argument, a holy wrestling. This type of lyric does not explain anything, says Fischer, but instead lets us feel something. If the poem is effective what we feel is the inarticulate sensation of universal human longing for the divine connection, and the grappling with its out-of-reachness.

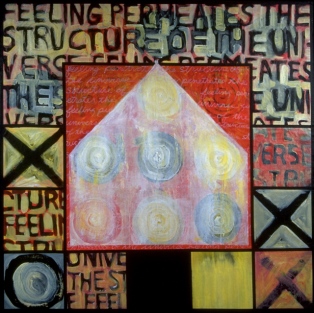

In the early nineties, before I’d heard of Bernstein or Fischer, I made a painting I called, Feeling Permeates the Structure of the Universe:

I was grappling with opposites, especially the seeming contradictions of will and feeling, intention and flow, logos and eros, meaning and emptiness. In this exploration, influenced by my typographer husband, I discovered words and letters anew: as entities that could convey, through shape, juxtaposition, size, color, and texture, a meaningfulness that existed in addition to their literal meaning. The opposites were not opposed, but intertwined. In the beginning was the Feeling that permeates and underlies the Word.

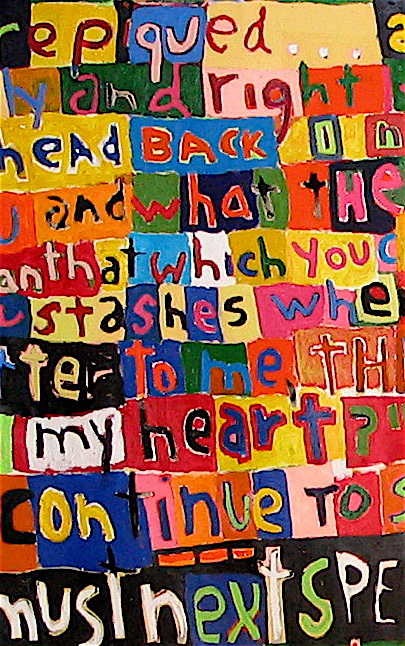

Around that same time, my friend, artist Joel Schapira, also started making paintings out of words. One of them, Letter from Jack Kerouac to Allen Ginsberg: Not Just Colorful Characters (14 feet x 8 feet), hangs in the student center at Naropa University:

Schapira’s Letter from JK to AG makes words into colors and shapes, figures on a ground, and separates the individual words into a grid of vivid bubbles that float off the canvas independent of their original context. The words of the original letter become like recombinant strands of DNA. Schapira allows different meanings to arise, form, and re-form, as our eye-ears connect the color red with red and “wHAt” with “frOM.” And, we are privy to Schapira’s wrestling: “my Alone, we must speak!” is what I overhear, what I read over Schapira’s shoulder.

Still, the letter Kerouac wrote, its ostensible meaning, is not totally obscured by the new revelations. Abstraction and representation live side by side, and even become one thing: Schapira abstracts the content of Ginsberg’s letter as he represents the shapes and forms of letters and words. Similarly, Bernstein’s utterance concretized (represented) the abstraction of the periodic table, revealing the feeling that resides within its seemingly cool structure.

The elements themselves, the periodic table of the elements, Bernstein’s poem of same, and the two word paintings inhabit the same generative universe, the place where we all live and look for the meaning we can never quite find or understand.

But this tension, too, can be reconciled, lived fully. Art has an even deeper purpose than the conveyance of ordinary meaning. It is “the pulling apart of meaning so that mystery can be revealed.”*

*(Thomas Moore, Dark Nights of the Soul, page 311.)